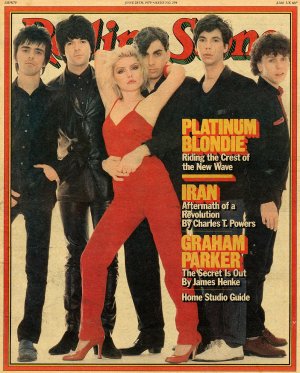

| Rolling Stone |

BOB ANDREWS looks like a middleaged

minister who's gone off on a bender at a church social. Dressed

in black pants, shirt and suit coat, the balding keyboard player

for Graham Parker and the Rumour darts around the dance floor

at the Agora Ballroom, jumping up and down, clapping and shouting

at the singer up onstage.

It's Wednesday night - "ladies'

night" at the Agora, a showcase-dance club located on a seamy

side street in the desolate downtown area near Cleveland State

University. The previous evening, a packed house turned out to

see Graham Parker and the Rumour, and now Parker and company are

back, doing a special show that was announced over a local radio

station only a few hours earlier. Unfortunately, because of the

short notice, the group finds itself facing not another crowd

of fanatics, as has been the case for much of this first leg of

Parker's three-month U.S. tour, hut a sparse, unattentive audience

of a few hundred cleancut college coupies who no doubt showed

up to hoist a few brews and listen to cover versions of late-Sixties

and early-Seventies hits performed by a local group called Lefty.

And Andrews is trying his best to set an example for the crowd.

"Get that heckler out of here," Parker shouts, pointing toward the

keyboard player. "He's been following me all over the country."

Andrews continues his antics, and Parker bends down to take swigs from

cans of Michelob and Miller offered up to him by the few faithful

at the foot of the stage. "Why do they call Cleveland the

rock & toll capital of the world?" Parker continues,

a sneer crossing his face. "What the fuck do they mean by

rock & roll-buzz-saw guitars or sornething? Well, don't worry, we'll

be doing our Beatles medley in a minute."

Instead, the Rumour rips into

a roaring version of "Soul Shoes." Andrews scurries

back up behind his keyboards as Parker prowls the stage like a

caged Leopard, occasionally stopping at the edge to lift Iris

large, tinted spectacles and peer into the eyes of the crowd.

By the end of the song, Parker and the Rumour have stirred up

enough enthusiasm that they are called back for an encore.

But it is still far from the

victory Parker had hoped to win when he agreed to do the

show for free. Backstage, Andrews begins talking about

the couples who walked out during the performance. "It

was the girls," he says. "Did you see them?

The kind who sit at home and watch the detergent and fabric-softener

adverts. The guys seemed to he getting into it, but their girlfriends

were grabbing them: 'Come on, Henry. We've got to get

home and do the laundry."'

Parker, slumped down on a

love seat in the dressing room, is not in a joking mood. "It's

depressing," he moans. "It's so fucking depressing."

GRAHAM PARKER HAS been waging

such battles against indifference for years. Born in 1950 in

London, Parker grew up in Deepcut, a country village in southeast

England. His mother worked in a cafe and his father was a coal

stoker. Parker left school when he was seventeen and began working

in the Animal Viral Research Institute, breeding mice and guinea

pigs. But he soon found that job, like most other aspects of

working-class life in England, a dead end.

His way of breaking through

that was music. In 1975, after a series of odd jobs and stints

in several bands, Parker, then a gasstation attendant,

sent a tape of some songs he'd written to London's Hope and Anchor

pub. Dave Robinson, who ran a recording studio there, heard the

tape, got in touch with Parker and matched him up with the Rumour,

an allstar band made up of veterans of England's then-waning pub-rock

scene.

The following year, Parker

and the Rumour - guitarists Brinsley Schwarz and Martin Belmont,

keyboardist Andrews, bassist Andrew Bodnar and drummer Steve Goulding

- released two albums. Howlin Wind and Heat Treatment

contain some of the most intense music of the Seventies, showing

off a variety of influences, from Bob Dylan and R&B to Van

Morrison and reggae. With Parker's growling voice pulling everything

together, it was clear that Graham Parker and the Rumour had risen

above pub-rock to create their own distinct brand of rock &

roll. As critic Greil Marcus put it: "Parker's advent was

a sign that the decade was finally toughening up: in its anger,

its lyricism, its sophistication, its lack of artiness, its humor

and its punch, his music cut a swath through most everything around

it." But despite the critical acclaim, those first two LPs

sold only 30,000 and 60,000 copies respectively.

The group and its management

put much of the blame on Mercury Records, their label at the time.

"Let's use Howlin Wind as an example," Allen

Frey, Parker's U.S. representative, told me over dinner the night

before the first Cleveland show. "We were out there touring

insupport of that album, which had such incredible reviews, and

here Mercury had done an initial pressing of only 8000 copies.

At that rate, youre lucky if there's even one copy in every city

you play."

(A Mercury representative

contends that although the company initially pressed 8000 copies,

"substantially more records" were in the stores by the

time of the tour.)

The third LP, Stick to

Me, released late in 1977, was not as well received by the

rock press, which criticized Nick Lowe's production, as well as

some of Parker's songs. And the two-record live set that followed

last year, The Parkerilla, was at best a flawed attempt

to capture the band's powerful live presence on vinyl.

The day of the second Agora

show, Parker defended Stick to Me. "I think it's

very hard sounding, very English sounding," he said. "It's

not meant to be played on an expensive hi-fi; I don't think it

works then, perhaps." He added that the album had originally

been recorded with producer Bob Potter, but that version was scrapped

when they found it was impossible to mix ("The hi-hat kept

going over everything, and there was something missing in the

bass frequencies"). The Nick Lowe version had to be recorded

in a week, crammed in between tours of Sweden and the U.K.

Parker did admit that The

Parkerilla was not as good as it should have been. But he

maintained that this was not because he rushed it out just to

fulfill his contract with Mercury - the reason most often cited

in the press. "There wasn't enough care taken on The

Parkerilla. I wasn't experienced enough, so I left it up to

my manager and whoever he got to do the sound. And I think we

botched it."

Despite his lack of commercial

success, Parker had no trouble finding a new label. In fact,

an intense round of bidding reportedly preceded his signing with

Arista Records. His first album for the label, Squeezing Out

Sparks, and the accompanying tour have gone a long way toward

regaining the momentum that was lost after the first two LPs.

The critical response has equaled, if not surpassed, that given

Parker's first two records. And at press time, the LP was in

the Top Forty with a bullet and had sold more than 200,000 copies.

In addition to being the first

album for a new label, Squeezing Out Sparks also marks

the beginning of a new rnusical era for Parker. The horns and

complex musical arrangements that had reached a zenith on Stick

to Me have been dropped in favor of a simpler, guitar-dominated.

sound. And lyrically, the album is his most introspective.

WHEN I ARRIVED in Cleveland,

it was immediately clear that this time around Parker was determined

to achieve the commercial breakthrough that had been predicted

for him for so long. In addition to the two Agora shows, he had

two radio-station visits planned (one to cut a station ID tape,

the other for an interview) plus a record-store autograph session.

The bulk of my interview was to be sandwiched between all of

these activities.

Parker is an intense, wiry

man who stands only five feet five and can't weigh a whole lot

more than a hundred pounds ("Everyone looks tall and fat

next to me," he joked during the photo session for this story).

My first indication of just how intense he can be came

the night after the first Agora show when we were discussing the

band's tour of Japan, which inspired at least two songs on the

album - "Discovering Japan" and "Waiting for the

UFOs" "It's really a weird country," Parker said,

taking a sip of Grolsch beer as we sat at the bar in Swingo's

hotel, just a few blocks from the Agora. "You go into a

bar over there, and they're eating raw whale meat. I mean, can

you believe that?" I offered a slight chuckle, thinking Parker

was going to joke about such odd food, when he added: "I

mean, fucking whales are going extinct, and here are these people

eating them!"

The next day we met in his

road manager's hotel room to talk about the new record. "What

we were trying to get across was the songs, the emotion, the lyrics,

rather than any kind of extravaganza," said Parker, who was

seated on the edge of a bed, busily rolling a cigarette. "In

the past, I occasionally found the music running away with itself,

and I was fighting in the middle of it. This time I wanted it

to be absolutely direct - the whole thing like a heartbeat. All

the riffs, like in 'Passion,' I wrote them with the songs. We

didn't elaborate on them much. I wanted it totally my show, and

that's why it's different. lt sounds like a Graham Parker alburn."

Parker gives much of the credit

for the album's more direct sound to producer Jack Nitzsche.

"The album took eleven days to record," Parker explained.

"It took two days to get the studio [Lansdowne Studios in

London] working because it had only been used by Acker Bilk and

things like that. The third day we rnanaged to play a song, and

Jack said, 'Come and listen to this.' There was just this big

mess corning out. So Jack and I went up to his hotel room and

I told him we wanted to get back to fundamentals but we didn't

know how to. I said, 'Jack, you gotta say what you think.' He

was a bit paranoid about criticizing the band. I said to him,

'Jack, we're English. We sneer, we're cynical, we're miserable.

But we really don't mean it.' So the next day we came in, and

anything he said, I said, 'Yeah, come on. Carry on. Wot? Wot?

Come on, say it. Here, have another beer.' And eventually we

got it out."

Parker nervously rolled another

cigarette ("Its an acquired taste. It's a little easier

on the throat," he said) and began to talk about "You

Can't Be Too Strong," the one song that perhaps best illustrates

the "less-is-more" production approach to Squeezing

Out Sparks. The song - done with just acoustic guitar, bass

and keyboards - is about an abortion that involved an intimate

friend of Parker's. lt has been praised as one of his most passionate

songs, but it has been criticized by those who feel Parker blames

the woman in the song.

"When you're sixteen,

or eighteen or something, you haven't got any money or anything,

and the only thing you can think about is, 'God, I only hope she

gets rid of it.'" Parker paused for a second and stared down

at the bed. "But I'm not eighteen now, and it just makes

you think .... But when I say, 'You decide what's wrong,' I'm

not putting any blame on a woman. I'm saying the fact is that

a man doesn't have to decide. A woman does. If it's saying anyone

is weak, it's the men, because they don't feel it."

The album's title also comes

from a line in "You Can't Be Too Strong." "That

title's the best one we've had," Parker said. "It means

death, for one thing. I mean, 'Saturday Nite Is Dead' - there

you go, you're squeezing out a spark. Then there's the abortion,

there's that level. Plus it's very sexual. And it's about writing

songs. You write a song, and you're squeezing out a spark. A

few people didn't like the title, including my manager [Dave Robinson].

He thought, 'What the hell is that? I mean, how can we market

it?' I said, 'l don't care. It makes people think.' l'm still

thinking about what it means. But you know what it's like in the

record business. 'Hit me, hit me, hit me. Give me something

I can market. - Stick to Me, something like that.' And

it's not quite that easy with this title."

As Graham was heating up to

the subiect of record companies, a representative from Arista

knocked on the door and told us it was time to leave for Record

Revolution, where the record-signing session was to take place.

"I mean, I just want

to make records," Parker concluded. "I want a record

cornpany to sell them - I want to be baked beans - a product.

You know, because I don't care. The record speaks for itself.

They ain't gonna change that. I think everyone should hear my

records and buy them. I don't think that's unreasonable. I mean,

I really don't think it is."

TWO WEEKS LATER, Graham Parker

and the Rumour arrive in New York for a show at the 3000-seat

Palladium. As we ride in the tour bus frorn yet another record-store

autograph session to a fire station where some photos are to be

taken, everybody's spirits seem to be rnuch better than they had

been in Cleveland. Squeezing Out Sparks is still climbing

the charts, "Local Girls" has just been released as

a single, and the tour has steadily been picking up steam since

the Agora shows. At one of three sold-out shows at Chicago's

Park West nightclub, the audience had refused to leave, dernanding

a third encore after the houselights had gone up. In Philadelphia,

Parker and the Rumour received a warm reception from some 12,000

Cheap Trick fans at the Spectrum, despite the fact that they had

not been advertised and that, because they got no sound check,

the sound was awful. And the band was ecstatic about the four

shows it had just played at Boston's Paradise Theater. "You

shoulda been there," Martin Belmont tells me. "I mean,

they were really incredible."

But everyone is still a little

nervous about the New York show, which had been sold out for weeks.

"We just don't want to jinx it," Bob Andrews says.

lt turns out they have little

to worry about. After getting off to a rough start, the band

begins to heat up around the time of "Don't Get Excited,"

the fourth song of the set. "Protection" follows, and

a good portion of the crowd is up on its feet. The next song,

"Mercury Poisoning," Parker's diatribe against his former

label ("The cornpany is cripplin' me/The worst trying to

ruin the best/....I've got Mercury poisoning/I'rn the bestkept

secret in the West"), is dedicated to Clive Davis, Parker's

new boss at Arista. The group then plays the title songs to its

first three albums, as if to let some more people in on the secret.

Onstage, the band forms a

visual hodgepodge. At the far left, Brinsley Schwarz, with his

neatly styled hairdo and white suit coat, looks like one of those

well-heeled college kids who turned up for the second Agora show.

He belies that image, however, with his occasional Pete Townshend-like

leaps and sudden bursts on his Gibson Flying V. On the opposite

side of the stage, Bob Andrews, the manic "minister,"

has a difficult time staying put behind his keyboards. He continually

runs to the edge of the stage to encourage the audience, then

dashes back to his station just in the nick of time. Martin Belmont,

standing to Andrews' left, brings to mind a young Keith Richards,

not only in his scraggly appearance, but also in his soulful riffing.

Inevitably, his lead break on "Don't Ask Me Questions"

draws one of the biggest cheers of the night.

But the focus of attention

is almost always Parker, whether he's slamming his fist into

his palm to bring home a point on "Mercury Poisoning"

or wrenching his face into a twisted sneer during "I'm Gonna

Tear Your Playhouse Down." As I watch him this night at the

Palladium, I can't help but think of something he had said to

the Cheap Trick audience in Philadelphia the week before, something

that just about sums up everything he and the Rumour stand for:

"This isn't a show," he said. "This is for real.

Don't you understand that?"

From Rolling Stone #294, 6/28/1979, p. 9, 23, 25 & 26

Back to GP article bibliography