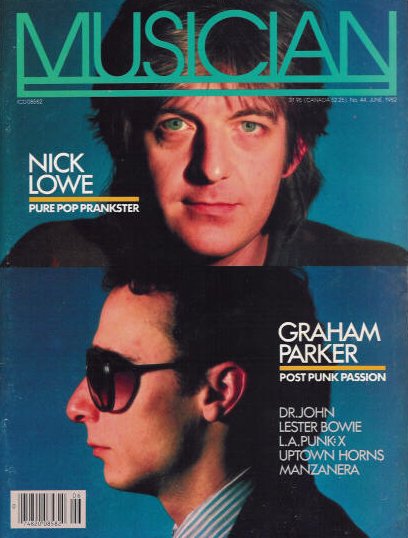

GRAHAM PARKER

On Graham Parker's last American tour, he and the Rumour visited Washington's Lisner Auditorium in 1979 with one of the greatest rock'n'roll shows this writer has ever witnessed. Wearing amber shades and a long, black, Merlinesque coat, Parker was a small, wiry man with a squirrel-like appearance. But as soon as drummer Stephen Goulding smacked his snare, Parker's whole frame tensed with urgency. He snarled and spat out the words with an anger almost inappropriate for a mere show. His claw-clutched hands scratched at the air as if trying to dig through the invisible barrier between himself and the audience.

The five members of the Rumour played with the same urgency. Brinsley Schwartz played slashing lead guitar against Martin Belmont's crunching rhythm chords; Parker followed their intro with a catchy soul melody. The band then shifted gears into hard-kicking rock'n'roll, and Parker shifted away from wry sarcasm into this furious admonition: "Passion is no ordinary word - ain't manufactured nor just another sound that you hear at night."

"Passion Is No Ordinary Word" from Squeezing Out Sparks is the essence of Parker's whole career. With a barely contained rage, his lyrics have attacked the fake emotions that dominate so much of pop music, indeed so much of life in general. His vocals and music are offered as an antidote, as a dose of something authentic. This has made him a critical favorite since his debut album in 1976, but has made him very difficult for radio to digest.

Parker's music is a strange but seamless blend of the Rolling Stones' rhythm guitar hooks, Motown's bouncy melodies, Stax-Volt's dance beat, Bob Dylan's nasal, ironic vocals, Van Morrison's grainy howl, Willie Nelson's austerity and Bob Marley's throbbing rhythm accents. Yet Parker doesn't so much sound like anybody as he sounds like everybody. All his influences are subordinated to the emotional directness of his songs. Thus they sound totally original and quite new. For all his traditionalism, he is often considered the founding father of England's new wave.

In the early 70s, Britain's pop music was dominated by bloated art-rockers and innocuous pop stars. A handful of London bands were playing a simpler, subtler music, a British version of the American country-rock of the Band, Little Feat and the Byrds. This pub-rock movement, as it was dubbed, included bands like Brinsley Schwartz, Ducks Deluxe, Chilli Willi, the Sky-Rockets and Ace. These bands made some lovely records, but precious little money. By 1975, most of them had broken up.

So by mid-decade, there was a feeling of both frustration and expectancy in London. Something had to happen. Then out of the blue came this kid from Deepcut, a suburb thirty miles outside of London. Parker played some acoustic, country-folk gigs with Noel Brown and Paul Riley. Then he sent a tape of his songs to Dave Robinson, the manager at the Hope & Anchor Pub. Robinson liked the songs and hooked up Parker with the newly formed Rumour (Brinsley Schwartz, Martin Belmont, Stephen Goulding, bassist Andrew Bodnar and keyboardist Bob Andrews. Disc jockey Charlie Gillett (author of the classic The Sound Of The City) played the tapes on the air, and Phonogram (Mercury in the U.S.) offered Parker and his crew a contract.

Nick Lowe produced the first album: Howlin' Wind. lt landed like a bombshell. lt contained twelve three-minute bundles of compressed dance beat, melodic hook and unmistakable honesty. Every cut reminded one of the hard-hitting beat and catchy melodies of the singles from Motown and the British invasion in the early 60s. Parker & the Rumour were joined by Dave Edmunds, Noel Brown and a five-man horn section. Howlin' Wind was followed with astonishing rapidity by Heat Treatment, produced by Robert John "Mutt" Lange. lt too was filled with compelling, horn-powered R&B tunes transformed by Parker's angry attack on false promises. Mercury released a spectacular live album, Live At Marble Arch, to industry insiders only at the end of 1976. In early 1977, Parker released a four-song EP, Pink Parker (named after the color of the vinyl) with two R&B covers and two cuts from the live album.

In one scant year, Parker had released two albums, an official bootleg and an EP. lt was a stunning outpouring, and it had its impact on other musicians. The results can be heard in Nick Lowe's production of Elvis Costello's first album, My Aim Is True. lt can also be heard in the anger and direct attack of the punk bands that followed in 1977.

Despite critical ecstasy, the two albums only sold thirty and sixty thousand copies respectively. Parker shifted his approach and wrote longer, more complex songs for his third album. They were full of cinematic imagery, which reflected his visit to America. We'll never know how they might have sounded, because the album, Stick To Me, produced by Mutt Lange, had a serious defect in the original tapes and had to be completely scrapped. Instead, Parker & the Rumour canceled a European tour, went back to England and rerecorded the whole thing in two weeks with Nick Lowe producing. The record reflects the sloppy, rushed, frustrated job that resulted. They went right off on tour, and Mercury released a live album, The Parkerilla, with Lange as producer. Not only were the performances far short of peak nights on the tour, but the sound was muddy.

By this time Parker was in a rage at Mercury Records for what he felt were promotion failures and sound tailures. He left the company with a legendary blast: a single called "Mercury Poisoning" with this scathing couplet: "I've got Mercury poisoning; I'm the best kept secret in the West!" He signed with Arista Records, which hired Jack Nitzsche as producer. Parker and Nitzsche huddled before the sessions to find a new direction for the singer. The result was the stripped-down, guitar dominated rock 'n' roll sound of Squeezing Out Sparks. lt is one of the dozen best rock 'n' roll albums ever made; the writing is often brilliant. "You Can't Be Too Strong" is an overwhelming ballad, encouraging a woman who has just had an abortion to be strong and not feel guilty. Squeezing Out Sparks was voted the best album of 1979 in the Village Voice poll.

About this time, Bruce Springsteen remarked that Graham Parker was the only singer he'd pay money to see. Springsteen went even further and made a rare cameo appearance as a backup singer on "Endless Night" from Parker's 1980 album, The Up Escalator, produced by Jimmy lovine. Though it inevitably suffered by comparison with the once-in-a-lifetime Squeezing Out Sparks, Escalator extended the sound and themes of Sparks. Like Springsteen and Bob Seger, Parker was wrestling with the problem of how to preserve the passion of rock 'n' roll youth in the face of eroding age and corroding society. "I had the energy but outgrew it/ The identity but saw through it/ I had the walk but got trampled/ Had the taste; it was sampled/ lf only I could find the switch/ That turns on the endless night."

Though his sales for the two

Arista albums had improved to the quarter-million mark, Parker

was still dissatisfied. He split with the Rumour after The

Up Escalator, and holed up for a year. Last fall he came

to New York to make Another Grey Area with producer Jack

Douglas and Douglas' studio musicians. Gone is the blustery,

all-out attack of the Rumour. In its place is a new clarity and

subtlety that reveals a whole new dimension to Parker's music.

The songs also reflect a subtler sense that his goals might always

be elusive, and that temporary victories and the struggle itself

must suffice in the absence of total victory. By the time this

article appears, Parker should be touring America with a new band:

guitarist Brinsley Schwartz, guitarist Carlos Alomar, drummer

Michael Braun, keyboardist George Small and bassist Kevin Jenkins.

The following interview took place over lunch in a midtown Manhattan

restaurant just after Another Grey Area had been released.

MUSICIAN: Do you still feel frustrated about not cracking the American top ten?

PARKER: I'd feel that even if I were in the top ten. Nothing is good enough. Even if I were number one, it would be that I wasn't number one long enough. And so on. The reason I do it is for hit records. That's what it's all about.

MUSICIAN: Why is that so important?

PARKER: Because that's what it's always been about. Not that I write songs for that. I write songs because they give me a thrill; they communicate with other people, and that's satisfying. But still it makes you mad when you see some of the bands who are on the charts apart from the Police and a few others. You get these girl singers who sound like Robert Plant and make old-fashioned music and you see them selling a lot of records. But I've accepted the fact that the public wants that kind of stuff. They want averageness. That's it, so you just keep making records.

MUSICIAN: No matter how much we may like Elvis Costello or Randy Newman today, pop music doesn't have the same universality, the same sense of community as it did with the Beaties and Stones.

PARKER: Yeah, right. You want a large audience. What a great feeling to know everybody's getting off on your music. But that's probably another illusion, because half of them won't get off on it anyway. They're just buying it because they're supposed to. But you feel better if you sell more on the new one than on the last one. The Up Escalator was top ten in England, and that made me feel great. It wasn't great enough, but it sold better than the last record, and it wasn't even as good as the last record. Imagine making a record like Squeezing Out Sparks, which I think is pretty hot shit, and it sells less than The Parkerilla, which wasn't the best recorded live album. You feel the frustration, because you know what you went through to make it.

MUSICIAN: You know how good it is.

PARKER: You think it is anyway. You get letters from people who say, "It got me through the hardest time of my life." lt really means something to people. But I accept the fact that I don't offer something easy. The way I sing is not really light. I don't pull the punches too often. If you hear me on the radio, I still stick out like a sore thumb.

MUSICIAN: What concessions are you willing to make to get that audience?

PARKER: None. I don't make any at all. I just write what I write. I can't preconceive it. I'm not interested. lf the public doesn't want to buy it, they don't. It's fair enough. I go out on the road to promote the album, right, that's my job. But the songs come out as they are. I can't adapt them in any way. Or make them more accessible.

MUSICIAN: Was the decision to work with a studio band and a producer like Jack Douglas an attempt to win a larger audience?

PARKER: No, I didn't even know who the musicians would be. I left it to Jack. The public doesn't care about production or a studio band or any of it. They just care about a hit song they can sing along to. If you listen to some of the records that are hits in England, the production or the playing is often pretty rough, but a lot of people still like it and buy it. I don't think it makes a shred of difference. When we made The Up Escalator, Jimmy lovine said, "This is going to be a big record, top five." You can't say that; you can't predetermine it.

MUSICIAN: Why did you split from the Rumour?

PARKER: I should have quit years ago, really. lt was just narrowness on my part. lt was easy to have a solid band there. lt was easy but it wasn't risky enough. A band can only play in one way. They can try and change, but you always know it's still the same band. About the time of Squeezing Out Sparks, I realized that I could have been making a good album with another band as well. I'm a solo artist, a lone wolf. lt should just be me and I should collect people for each record. But I don't know any musicians, you see; I don't hang out with musicians. One of the reasons I picked Jack Douglas to produce the new album was he convinced me not to worry about musicians because he could get a good band. The only person I knew I wanted to use was Nicky Hopkins, who had played on The Up Escalator.

MUSICIAN: There must be advantages and disadvantages to having the same band year after year. On the one hand, they understand you and you understand them, but on the other hand, you end up doing much the same thing again and again.

PARKER: Yeah. Graham Parker & the Rumour got to a point that was incredible in one way. We did three shows after The Up Escalator: two at the Hammersmith Palais in London and the Rock Place Festival. It was the best gig I've ever done on TV. When you have a band like that, you get tighter and tighter, and it gets better and better as a live act. You can't reproduce that in a number of weeks or tours with a new band. You just can't. But with a new band you're taking risks; you're going to have more excitement, and you're not getting stale. You have to work harder. I can be as lazy as the next man.

MUSICIAN: Did you find that the Rumour would take your song and make it sound like themselves?

PARKER: That always happened. We were always friends, and when we started off, I was a total amateur and they had more experience. I didn't know how to arrange musicians. I didn't listen to drums. When someone said, "All the high-hats are there," I didn't know what a high-hat sounded like. All I ever heard was a song and if it gave me a thrill. Bob Andrews was a great help in the beginning. He could take a song and change it completely to make it work. I dug it; it was okay and it worked, but it was the Rumour playing Graham Parker.

MUSICIAN: Then it became as much their song as yours?

PARKER: That's right. lt would become the band's arrangement. But over the years, by the time we got to Squeezing Out Sparks, I was totally controlling it.

MUSICIAN: What had changed?

PARKER: Just experience, that's all. I realized, wait a minute, sometimes I hear our records after they're made, and it sounds more like a lot of people fighting than a record being made. That's what it was like to me. If I listen to Stick To Me, it sounds like a pitched battle. Every hole in the record is filled with either a bass going boom-boom-boom, or a guitar that howls. It's all very frantic and frenetic. People loved it; that was Graham Parker & the Rumour. But it doesn't mean that is Graham Parker. That's just one aspect.

MUSICIAN: How did things change when you and the Rumour did Squeezing Out Sparks with Jack Nitzsche producing?

PARKER: I just realized that I wasn't satisfied with making the same record every time, where it fell into place, where I'd just sort of go along when somebody said, "Why don't we do a number this way or that?" I didn't want to do that. I had to have something different, because The Parkerilla was the culmination of Graham Parker & the Rumour live. After that I just had to have a different sound. A different outlook. So Squeezing Out Sparks was a logical step. lt was stripped down to the bare, dry bones. This all came out in my discussions with Nitzsche before we recorded. I said to him, "I don't care whether it's like Phil Spector; I don't care what direction it takes, as long as it's different and more direct." It had to be more direct. I didn't want the drums to be all over. Stephen and the rest of the band had always been encouraged to play too much, because we always seemed to have producers who loved "Graham Parker & the Rumour." They loved the band. Jack Nitzsche didn't love the band. So that helped. He didn't even love me. He didn't know who I was. Until he heard the songs. He knew of me. "What's all this new wave stuff about," he said, "what's it mean?" When he got into the songs he really loved them. That's when he and I started to communicate and take hold of the whole thing. Jack said to me, "There's more ego in this band than in any band I've ever seen." And this is the Rumour. I said, "But you were with the Rolling Stones." And he said, "What are you talking about? There's no ego in the Rolling Stones. They play the song. This band doesn't play the damn song." So we had a bit of a crisis at the beginning of Squeezing Out Sparks. I said, "Look, you're the producer. I'm Graham Parker. You help me, and we'll tell them how to play. We'll make a different record from my last one." And from then on, that was it. His main focus was Stephen. He told me, "Stephen's playing all these cymbal splashes and it's falling all over itself. All that splashing is exciting live, but on record it's just a fizzy sound." I said, "I know, but I don't know how to change it. You're the producer." Now I could. I'd just tell the drummer, "Just hit the beats; just hold it there," and I'd tell the bass player, "Be the bass; don't be the lead; just be the lead when you need to be." But then I needed Nitzsche. So he told Stephen to get on the high-hat instead of the cymbals and everyone else to hold onto the basic chords and stop trying to be so clever.

MUSICIAN: lt was more a matter of telling them what not to play than what to play?

PARKER: What not to play, right. Less is more. It's as simple as that. Then Nitzsche asked me, "Listen to your song. What do you want on it? Do you want dancing girls? Hand claps? I can put all that on it. I can put a million tambourines on it; I can add acoustic guitars. But what do you need? Listen to the words. Are you serious about these songs?" I said, "Yeah." He said, "So that's it. All you need are four or five instruments." There was very little overdubbing. We'd play live, get the basic thing, and go back and repair what was messed up. It was real easy once we found the direction.

MUSICIAN: Even though you'd established some discipline on the Sparks album, you felt you needed a complete break?

PARKER: Yeah, The Up Escalator was good. It was what I wanted. It was still in the right direction for me. lt was still more direct, and I had as much say as I'd ever had, totally telling them to play this or play that. But I still needed to take a risk after being with the same people for five years. So just after we did that Rock Palace show in Germany, I said it's time to call it a day.

MUSICIAN: Why is it hard to stay together?

PARKER: Well, you just get up people's noses. And the Rumour are friends; we get along great compared to most bands, I'm sure. But that's all there is to it. We just get up each other's noses, and they can do other things. They're big boys.

MUSICIAN: So the split was amicable.

PARKER: Yeah, they knew it was probably about time.

MUSICIAN: It seems that Another Grey Area extends the simplicity and clarity of Squeezing Out Sparks even further

PARKER: I'm singing better, that's all it is. I've always been striving to make a record that sounds beautiful. I think Another Grey Area sounds beautiful. The records I play at home are by Steely Dan and Paul Simon, and there's a Bobby Bland record I play called Dreaming with "Ain't No Love In The Heart Of The City" on it. I play Lowell George's solo album, Thanks, I'll Eat lt Here. Now that to me is a great-sounding record.

MUSICIAN: What do you mean by beautiful?

PARKER: I mean the perspective is just full. Everything is in the right place. It's not a question of sound. When I say sound, I mean putting instruments in the right perspectives, so you get a bass in the slot, so the whole thing holds together.

MUSICIAN: There's a certain symmetry....

PARKER: Yeah. Some of my records haven't had that. Everytime I make a record, about six months later it sounds terrible to me. When I hear Squeezing Out Sparks, all I hear is the bass drum. lt's louder than the bass. I know that actually it's a good record, but I'm still not satisfied with it. But Another Grey Area still sounds like it has that symmetry. Everytime I hear it on the radio, it still sounds like a great-sounding record. Whereas, I hear "Fool's Gold" from Heat Treatment, and it doesn't sound like a great-sounding record. lt sounds muffled.

MUSICIAN: At the same time, the words you wrote for "Temporary Beauty" are no less angry and no less cutting than those you did with the Rumour

PARKER: Right, they're not, not at all. "Big Fat Zero," "Another Grey Area," they're all put-downs. Just the same as the other records have been. In England, the critics are panning it. They hate it. Because they're prejudiced. They've also missed the point of the lyrics. They think the songs are cop-outs, but they're not listening. They're listening to the fact that there isn't Graham Parker & the Rumour with the band being angry. You made the point exactly: the band was playing angrily as well and it wasn't necessary.

MUSICIAN: I thought the Rumour were great, but this new approach reveals a whole different dimension.

PARKER: Sure, it was great. I'm not putting it down now. I'm just trying to illustrate why you go from one thing to another. You O.D. on something and you go to somewhere else. I'm not a static artist. I'm not in a fixed position.

MUSICIAN: You're listed as co-producer on the album. How much production did you do?

PARKER: I just shouted a lot really. On my last two albums, I saw that production isn't just twiddling knobs. I don't know anything about control boards. But I have learned about perspective and the dynamics of sound, so I talked a tot. But the sound is Jack Douglas'. If you listen to Double Fantasy and Another Grey Area, you'll probably notice the similarity in sound. On the last few albums, I've been involved with some of the leading producers, so I figured that maybe I should be calling it co-production. After all, Nick Lowe, who taught me recording, is a producer. Most of the time, he just goes, "Yeah, louder! Great vocal! Yeah!" He's a primitive. That's where I learned it from: "It's missing the point.... Do it like this.... Give it a bit of this; change the rhythm; play it backwards; do something." He calls himself a producer, so why can't I?

MUSICIAN: You said you feel you've become a more skillful singer on this album.

PARKER: Well, I've improved my singing on every record, just by not being satisfied with my voice on any album I've made. I'm just hitting the notes right. Jack Douglas was great, because he didn't care about Graham Parker singing "Yah, yah, yah!" He didn't care. He just let me sing. "Temporary Beauty" is a live vocal, the whole thing. I just did three takes and the third one was the take. It's a technique of learning - not studying - to sing. You sing more and more, and instead of singing with your throat, you're singing with your chest.

MUSICIAN: How much of it is premeditated? Do you know which lines to sing clearly and which to sing gravelly?

PARKER: lt just evolves as you sing the song. As you're rehearsing with the band, it gets locked into your head. I'm totally instinctive as a singer.

MUSICIAN: lt seems as if the non-shouting, non-grittyside of your voice has developed over the course of your career. It seems like you're doing a lot more of that now.

PARKER: Yeah, because when I first started, the first thing you did as soon as you finished an album was go on the road. I'd lose my voice on the first gig. Shouting was a way of over-compensating for the fact it wasn't right. Everyone was saying how great it was, but it wasn't great. lt was awful. After three years on the road, I got more professional, the Rumour got better, the sound balance improved and I could finally hear myself. We finally had enough money to afford good monitors. When you start off, you have nothing. You're just scraping through, and the anger and aggression got us through. And that was right for the time.

MUSICIAN: Who were your models as singers?

PARKER: Originally, it was people you obviously know, like Van Morrison, Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan. If you listen to Howlin' Wind, you can tell they were the main three sources. Now I'm not so impressed by those people. It's like a long time ago. I'm impressed by very few people.

MUSICIAN: Anybody?

PARKER: Smokey Robinson. I liked him years ago, but not much. I preferred the harder singers like Otis Redding. Now I think Smokey Robinson is the best singer on the planet. It's pretty weird, all the people who have been around since him, and I think he's the best singer. I don't think he makes the best LPs, but I get inspired by the occasional record, like "Being With You." I was inspired by that. That helped me sing this album in a way. I saw him in L.A. recently. lt was just amazing; the guy sent shivers down my spine. He's a great artist. If you could hope for just one jot of what he's got, then you're hoping for something.

MUSICIAN: Even though it comes across a bit differently in Another Grey Area, anger has always fueled your records. Where does all that anger come from?

PARKER: I don't know anymore. That's why I don't like to explain my lyrics anymore. Just getting through the day is enough to make you want to write something angry. It just comes from everywhere. I just walk down the street and see the way people treat each other. Or in any kind of relationship. It's just one side of life. It's just that I can't sing about jolly things very easily. I can't write about them. Some people can. Like (sings) "Groovin'...on a Sunday afternoon." I wish I could write a song like that. That's fantastic. It walks the thin line between rubbish and great because of its subject. How can you write that? But they did, and it's great.

MUSICIAN: On the new album, even though there's still a lot of frustration about not getting everything you want, there's also a more reflective sense that maybe no one gets everything they want. Sometimes you have to make do with "Temporary Beauty." Get it while you can. You can't always get what you want.

PARKER: Yeah, that makes sense. I'm a very happy person basically. Yeah, I have a pretty damn good time. People write about me: "This man is the most morose, miserable S.O.B. in the world," but I ain't. I just express that angry part that everyone else goes through but they can't put into words as well as I can. Everyone feels the same kind of things. I ain't different from anyone else.

MUSICIAN: When you were growing up, what role did music play in your daily life?

PARKER: Well, it was just more interesting than going to school. You realized you had to play the guitar and be like those people. Then when I was seventeen there was soul music and bluebeat and ska, though it was underground. It just struck a chord in me. It reminded me of what the Swinging Blue Jeans and the Beatles were doing when they started, when it was tough and raw. It was what counted. It was better than Cliff Richard, Lulu and those people.

MUSICIAN: Did you feel part of a special group that knew the bands and the dances?

PARKER: Yeah, when I was a mod, obviously. lt was exclusive. Nobody else knew about Prince Buster & the All-Stars.

MUSICIAN: Why was it important to know something no one else knew?

PARKER: In England you have a youth culture. As far as I remember we always have. In America I don't see it as much. It was important to be different from adults and from people who didn't dress as good as you did.

MUSICIAN: Why was it important? What were the alternatives?

PARKER: The alternative was being a bozo. You were hip or you were a bozo. You felt good if you were in with the in-crowd. (sings) "I'm in with the in-crowd." We used to go hear that record and we knew what he meant, even though he was a black guy who didn't know anything about us or our dances. But it meant the same thing.

MUSICIAN: Were you able to sustain that after you got out of school and had to take a day job?

PARKER: No, when I went to work, I just forgot about music. I thought maybe it wasn't a serious thing. Then I gradually realized that work wasn't a serious thing, so I got back into music. Anytime I've forgotten about music for a bit, it's only been temporary. It's just a driving force.

MUSICIAN: But obviously you were the exception. Most people abandon their passion for music as they get older and get jobs. Why don't they hold onto that passion?

PARKER: No idea. They just lose it. My friends went through that. They stayed in their straight jobs and I didn't. They think it's more serious to get a job and get married. There's no alternative for them. How can they still be a part of it? It's very hard. You can't gain anything from it apart from fun. You can't get through life on fun; you have to earn a living.

MUSICIAN: lt seems a lot of your songs are about that, about keeping that spirit alive past that age barrier.

PARKER: Yeah, you're right, they probably are. But they ain't going to listen to that - though it may change people's lives a bit. Fans have written me letters and said, "I heard your song and said, "Screw it, I'm giving up my job. That's it. You're right.'" So I've actually reached some people. It's unbelievable.

MUSICIAN: Isn't that why it's important to have a large audience?

PARKER: Sure, the more people you reach, the more who are going to say, "Yeah, screw it." There is an element of chaos in it. An element of internal revolution at least. But society won't allow it. The class system in England still has a total stranglehold. They'd like people who have a poor education to keep on having a poor education. They want them to fill the slots and do the dirty work. They don't want them to be inspired. They don't want them to make a living out of something creative or exciting. They want to crush them every step of the way.

MUSICIAN: How did that affect you personally growing up?

PARKER: That's probably why I wrote songs. I could see it happening all around me, and it wasn't going to happen to me. When I first got a job at seventeen, breeding animals in a research laboratory, that was going to be my career. I was interested in zoology and biology. But I soon realized that you had to have a pretty heavy education to do that. Being a working class person, there was no way I was going to get to do it. All I was going to do was look after these animals that were going to be killed and vivisected by someone else. So that's quite a mindblower when you realize that: they ain't gonna let you. The only way I could be educated was by going out into the world and finding out what made it tick and educating myself. So that's what I did.

MUSICIAN: In America at least, your first album was lumped in with a// the new wave stuff that followed, even though it preceded the punk explosion by a year. Was that appropriate?

PARKER: Sure, it was appropriate, because they were saying this is the beginning of something new and so was I at the same time. I played for audiences who didn't know what I was doing. lt was like I was from another planet.

MUSICIAN: Do you feel you paved the way for new wave?

PARKER: Definitely, there's no doubt about it.

MUSICIAN: Do you see the influence of Howlin' Wind on Costello's My Aim Is True?

PARKER: Yeah, to a point. But I think he was doing the same thing at the same time anyway. The fact is, there were a lot of people in London at the time who didn't believe they could become anything because of the way things were. Meanwhile I was out in Deepcut, thirty miles outside of London. I wasn't playing in the pubs and seeing how useless it was.

MUSICIAN: You didn't know any better?

PARKER: I didn't know anything. I came along and said, "I'm great. I'm going to be big. Listen to this." That took a lot for me to do, because I'm not that kind of person. I'm pretty humble about it. But I realized I was writing better songs than I heard on the radio, and I was going to other sources to get the songs: country, blues and reggae and bringing them together into modern music. I was the first one in that whole scene apart from Ace and Dr. Feelgood, who did a similar thing. Dr. Feelgood was the first new wave band.

MUSICIAN: The punk stuff that followed your album was a lot different from your music. There was a similarity in the anger and the directness and the attack on melodrama. But yours was really rooted in tradition with lots of melody and swing, whereas the other stuff was very unrooted with almost no melody or swing. What did you think of the punk stuff?

PARKER: I like the Sex Pistols a lot. It's hard not to; they made some amazing records. But most of it was crap, really and truly. Most of it was people cashing in, because here's the new thing. They may have liked it, but only a certain amount of people have the talent to do it like the Clash or the Pistols.

MUSICIAN: Do you think there was that distinction between new wavers who had that pub-rock sound like you, Elvis, Nick, Joe Jackson and Squeeze, as opposed to hardcore punk bands like the Pistols, Clash and Jam?

PARKER: Yeah,

there was. There were people who hated me because they were so

hardcore. The Sex Pistols and them had a definite style; it was

drone music - loud and screaming all the way through. And there

were people who didn't like that and liked me because they thought

it was more serious or something. And there were people who didn't

like any of it. I didn't mind being lumped in with the punks,

because they took over England in a way. Being called the godfather

of punk or stuff like that was not too offensive, because I'd

rather be lumped in with the new fashion than the old-fashioned.

| Dark Side of the Bright Lights

I never played lead guitar with the Rumour - only on "Mercury Poisoning" onstage. But on this new album, I played a lot. I did every guitar part on "Hit The Spot," which was a great thrill for me, I couldn't have done that with the Rumour. It would have caused problems. But my rhythm guitar is all over the new album. I have a Fender Telecaster that Nick Lowe sold to me a long time ago - a 1959 Telly, a real old, yellow-colored thing. I got my Gibson 303, which isn't bad for a guitar with a warped neck. I managed to use it on this album. We said "primitive," right? I've got two Ovations, one that I used on the album. I've also got a Martin acoustic and a Guild. Brinsley Schwartz has a couple of Hamers that were made for him. He's got a black one, an orange one. He's got a little tuning device put in the black guitar so a light comes on when you hit a string and it's in tune. Otherwise he's using very simple gear: a Mesa Boogie amp with a couple of extension speakers. I'll just go with a Gibson Lab amp and a Music Man, and that should cover me. |

PARKER: I knew there was no way music was going to be on just one dimension and stay there. Music will always be many different things.

MUSICIAN: Why do you value those older traditions?

PARKER: Because they're classic. They're modern, and they're old. They're timeless. While "Anarchy In the U.K." has its place in time. When I hear that, I think of a particular time.

MUSICIAN: Are there any recent records that you like a lot?

PARKER: I just heard that single, "Why Don't You Want Me" by the Human League. I just love that catchy chorus. I like hearing Nick Lowe's records. Squeeze. Elvis Costello. He's the greatest; he's really brilliant. I like the Clash's Sandinista! I didn't get the album, but I hear it on the radio and the tracks are great. They're really doing something different. You see, they didn't stick with what they were supposed to be either. Sandinista! got heavily slagged in England, but I think the public liked it because they were doing something different and going into more avenues of music. The Talking Heads' record, Remain In Light, that's sensational. I played that for a long time when it came out.

MUSICIAN: On songs like "Passion ls No Ordinary Word," you imply that so much that passes for real emotion in people's lives isn't real emotion at all and that your music is striving for some authenticity. Why is that such an important issue to you?

PARKER: People are dull, aren't they? People aren't living to their max, or to anywhere near it. They're just drones or clones. Especially in England - they're just walking zombies. They believe what the TV tells them. They're just put in a direction and led there.

MUSICIAN: Do you think they're stupid or just manipulated?

PARKER: No, I'm talking bullshit really. I think everybody has great potential to understand. I think probably they should all take LSD or something. I did it at one point. It helped a lot of people. People have more potential than they're given credit for. I found that the dullest people who are stuck in their job, who believe in TV, can be woken up. I mean, I've known people who believed that peanuts are made in a factory. I'm not kidding you; they didn't know they grew. But when you talk to those people, when they hear a song and listen to it, when they're introduced to new things, they have fun and start to work on different levels.

MUSICIAN: In your lyrics, you attack both the people who are doing the oppressing and those who are letting them get away with it.

PARKER: Yeah. Don't you get frustrated when you see all the money being spent on the military, and the public goes, "Ooooh, boy, yeah, sure." They know what's happening. They're powerless, but they're not. You feel there could be some chance of doing something about it. At the same time I hate organizations. I hate people who say, "We got to stop this nuclear stuff," dead serious. So really I don't think we'll get anywhere. If I got my way, no one would get anywhere. There'd just be chaos. But it would be fun, more exciting.

MUSICIAN: So you don't think you'll ever write explicitly political songs?

PARKER: No, I don't think so. lt might be fun, though, maybe

I would. If Dylan got into Jesus, anything's possible. After writing

all that incredible

music, he went into that direct preaching. Religion was always

there in his songs, but for someone you think is the most far-out

person in the world to say, "I'm a born-again Christian,"...

I mean, if he can do that, anything's possible for me. I could

be leading an anti-nuclear demonstration tomorrow. Or a pro-nuclear

one. I'm full of contradictions. Whatever I say now, it's bullshit,

because tomorrow I'll say something different.

Copyright 1982 by Geoffrey Himes from Musician #44, 6/1982

Reproduced with kind permission from Geoffrey Himes.

Back to GP article bibliography