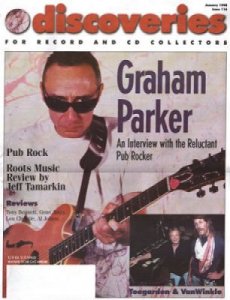

Copyright 1997 by Dave Thompson from DISCoveries #116, 1/1998

Reproduced with kind permission from Dave Thompson.

Back to GP article bibliography

Copyright 1997 by Dave Thompson from DISCoveries #116, 1/1998

Reproduced with kind permission from Dave Thompson.

Back to GP article bibliography