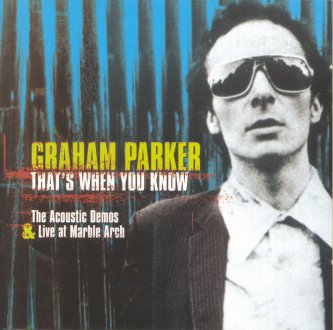

THAT'S WHEN YOU KNOW, Mercury/Universal 540 603-2, 7/2/2001, UK

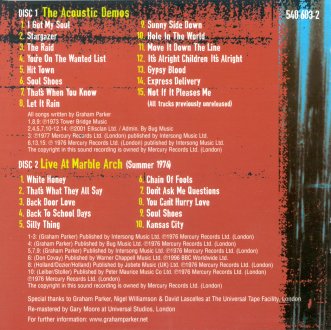

DISC 1 THE ACOUSTIC DEMOS

Some years back, a bunch of my demos from the early 70s surfaced, much to my embarrassment. These tunes were recorded for a publisher I'd signed with before I really hit my stride and as such, feature songs that jump through a variety of styles and portray an artist who is not sure whether he wants to be James Taylor, Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones or Ravi Shankar. Formative stuff - and I winced when a tape came my way, groaning loudly at the sight of the titles alone.

I assumed that with this release (luckily not an official release but merely cassettes that hard core fans were circulating) the decks had been cleared, so it was with some surprise when my contact at Universal sent me the collection of demos included here.

Some of the titles were recognisable as having come from the previous batch of material mentioned above, and some were songs that made it onto Howlin’ Wind. But there were six titles that I had no memory of at all. ‘Stargazer’, ‘You’re On The Wanted List’, ‘Hit Town’, ‘That’s When You Know’, ‘Move It On Down The Line’ and ‘It’s Alright Children It’s Alright’ did not ring any bells and it was with some trepidation that I fired them into the turntable and gave them a spin.

Ouch! Ouch! Ouch! Doh! Ouch! And Ouch! again were pretty much my reactions.

‘Stargazer’ has all the excruciating hallmarks of my early 70s Moroccan period, that lonely-boy-on-the-road-and-in-the-bedsit thing so typical of the era’s troubadours, albeit with a fairly strong melody. ‘You’re On The Wanted List’ has an inkling of the pop sensibilities I would soon thankfully employ, but ‘Hit Town’ is just plain awful, completely unsure of what it is supposed to be.

To he honest, I'm quite fond of 'That's When You Know', a number that combines the Van Morrison / Dylan leanings I would work with later on. Move It On Down The Line' has a pleasant if hackneyed chord progression but totally unfocused lyrics. and 'It's Alright Children...' well, the less said the better really.

A couple of other surprises pop up here too: I knew I'd written a song called 'Hole In The World' because when I periodically meet up with an old pal of mine from the suburbs, the rotter always mentions the tune as being one of his favourites, ignorant as he is of all the sterling stuff I've written in the intervening 25 years.

'Express Delivery' is a song The Rumour and I actually played live at least once: a tape circulates of one of our earliest performances at London's Newlands Tavern in which we bash through a fairly passable version. Here, in solo form, it still has a pleasing jaunty nature and uses the open E tuning used to better effect with more successful compositions like 'Gypsy Blood' and 'Soul Shoes' also included here in rough form.

A part of me hopes that with the discovery of this session the decks are now finally cleared. Another part of me, however, enjoys the thrill and uncertainty of discovery, that exquisite embarrassment experienced when a piece of the past appears unexpectedly and slaps one across the face like a wet fish.

I expect the world of studio archaeology has more in store, somewhere down the line some other interesting artefact will surely pop up. Until then, have fun with these tunes. I already am: I'm working up a version of 'That's When You Know' for my next solo performances and considering the possibility of recording it with a band someday. It holds up quite nicely, as it happens.

Graham Parker 2001

It’s a difficult decision for any artist. Should demos and out-takes which were never intended for public consumption at the time be released a quarter of a century later?

As a fan, of course, there is only ever one answer. It is endlessly fascinating to catch a glimpse of the formative creative processes of any great artist and to hear previously private work-in-progress, whether it's early versions of songs that subsequently became much-loved in another form or compositions that were briefly worked on before being cast aside. After some considerable soul searching, Graham Parker decided that he really had nothing to hide and agreed to share wuth the world these 15 early acoustic demos recently found in the record company’s vaults. Recorded in early 1975 – probably in the small studio run by Parker’s first manager Dave Robinson above the Hope and Anchor pub in north London – several of the songs will be familiar in other versions. SOUL SHOES, NOT IF IT PLEASES ME and GYPSY BLOOD all ended up on Parker’s classic 1976 debut album, Howlin’ Wind. All these versions give us an intriguing insight into how a great song begins to take shape. Another song, THE RAID, surfaced a couple of years later on the third Graham Parker and The Rumour studio album, Stick To Me.

Others will be completly unknown – and there are several here that even Parker himself does not remember – although he has himself delighted to renew acquaintance with at least one of them and has recently rescued THAT’S WHEN YOU KNOW. He had to relearn both the chords and the words but the song is now part of his live set again for the first time in more than a quarter of a century.

Several of the songs are a hangover from Parker’s hippie days in the early 1970s. "I decided I wanted to be James Taylor, which was pretty embarrassing. But later I got into Dylan and Van Morrison in his Tupelo Honey and St Dominic’s Preview period and the Motown and Stax soul infatuation started caming back to me. All those influences are there in the demos."

But whatever his misgivings about some of these early songs, the demos undeniably capture Parker at a critical time in his musical development – and therein lies the fascination. "Suddenly I found that I could write serious songs that were three-and-a-half minutes long with a beginning, a middle and an end. They had influences but they weren’t a copy anymore. They were really me. So there's some interesting stuff on there.' he says modestly.

What is perhaps most surprising is the hint of insecurity in the voice, given that Parker's vocals were soon to become famous for their unrestrained aggression. "That is odd," he agrees. "Because at the time I was probably very arrogant. I thought I was the only one who knew about this music and I was the Man. But it's a very schizophrenic thing, being a performer. Sometimes you feel like a God and other times the little boy comes out in you. On the demos you can hear quite a lot of the vulnerable, fragile little boy. Which is excruciating - but kind of nice." Yet there's no doubt that the intimate insight these demos offer into how a skilled songwriter hones his craft and a great performer discovers his voice can only enhance Graham Parker's reputation as one of the finest singersongwriters of our age.

Even Parker has softened towards them since his initial horror when the recordings were first rediscovered. "I still regard myself as a contemporary artist and I've just recorded a new album which is full of devilish tunes," he says with all his old brio. "But I can't deny it's fun to go back and listen again to how it all started."

Nigel Williamson

DISC 2 LIVE AT MARBLE ARCH

Phonogram had signed me to my first record deal, and according to my manager, I needed to get over to America as soon as possible, either because here was a nation of very out-of-date youth who needed saving, or because there were lots of chicks who couldn't resist blokes with English accents. I can't remember which one it was now, but both missions seemed to make sense.

And so, in order to score on either count, it was necessary to secure a deal with Mercury. Phonogram's American counterpart. This apparently meant impressing a lot of really old guys in suits who were quite happy selling middle-of-the-road compilations to very large people in the Midwest, but who would, no doubt - after witnessing a mere 37 minutes 48 seconds of lacerating English R&B performed at breakneck speed by a bunch of angry yobs who were (judging by the aforementioned velocity of our performance that day) actually on speed - reach for their wallets and sign GP and the R to that most coveted item, an American record deal.

Unfortunately, those old duffers went for it like rats up a drainpipe, and our almost absurdly intense show, recorded for this strange (but conveniently captive) audience in Phonogram's Marble Arch studio apparently impressed the heck out of them, and the immediate American release of "Howlin Wind" was assured.

I say "unfortunately", because it is a matter of history (nay, legend) that we were picked up by Mercury and within minutes of setting foot on US soil became a constant, if minor irritation to those grey-haired old sods who had no intention of promoting, advertising, payola-ing, or any of the other "ings" necessary to effectively reach an American audience of more than ten people.

To save money on a photographer, for instance, Mercury’s idea of a seductive shot of me was to take one of those record store display cardboard cut-out things that had somehow found its way across the Atlantic, and take a photograph of it! They then got their art department to apply a bit of white-out around the haircut which resulted in a picture of Yours Truly sporting a bizarre and gigantic pompadour, looking like a fugitive from a Mink de Ville line-up. That shot plagues me to this very day.

It may, with any luck, grace the inner sleeve of one of this series of CD reissues and you can all have a good laugh at my expenses. Many’s the time I’ve returned up for a club date, even in recent years, only to notice with horror that that very shot is pasted up outside, my head still resplendently couched in a sea of whitest white, my barnet stubbornly coifed as if I am about to be interviewed to join the Scots Guard.

With an image like that, it amazes me that I’ve managed to stay out of a day job for 25 years.

Graham Parker 2001

Graham Parker and The Rumour had revitalized British music with their debut album Howlin' Wind. Released in April 1976 to a wave of enthusiastic reviews that had compared Parker to Van Morrison and Bruce Springsteen, his raw and energetic vocals combined with his intelligently crafted songwriting had come at just the right moment.

Indeed, at the time Parker appeared to be the saviour of British music. The amiable sound of pub rock was beginning to sound distinctly limited in its ambitions and the punk hordes were massing on the horizon for their trail of havoc and destruction. Parker was in many ways the bridge between them. But the next step was to sell his soulful, r&b style to America.

Parker and The Rumour were always a dynamic live act and had just completed successful tours supporting Ace and Thin Lizzy. They had got their chops together, as the saying goes, and were in blistering form and at the top of their game. The logical move to sell the music across the Atlantic was to invite potential American record company suitors to witness for themselves the high octane, red hot, no holds barred experience that was Graham Parker and The Rumour live. Accordingly, one day in the summer of 1976 a small group of label executives who had flown in from New York to be there were assembled in a tiny studio near London's Marble Arch where Parker and his backing band performed a 'showcase' for them.

It was a bizarre occasion, as Parker recalls. It was the middle of the afternoon and while outside the streets were thronged with shoppers and tourists, inside the studio without a crowd at all, the atmosphere was non-existent. Yet Parker and the band triumphed. They were signed immediately to Mercury in America and the tapes of the gig sounded so good that they were released as an official bootleg in a pressing of just 1,000 copies which became a much sought after collector's item.

That Parker and the Rumour were able to summon tip such fire and aggression in such an antiseptic environment was remarkable. The performance was quite possibly chemically enhanced ("we sound like we were on speed", the singer admits). But the absolute sureness of Parker's vocals is all the more astonishing when you hear him describe the naivete of his approach back then.

"I had absolutely no stage craft because I hadn't really paid my dues. I kept losing my voice all the time because nobody had taught me how to warm up. I just used to scream, but when I sung with a shredded voice people only seemed to like it all the more," he recalls.

The Marble Arch set consisted of five songs from Howlin' Wind, two from the forthcoming second album Heat Treatment plus a couple of daring covers - Don Covay's CHAIN OF FOOLS, which was, of course, immortalised by the great Aretha Franklin and the old Motown classic YOU CAN'T HURRY LOVE. "That was shock value," Parker says today. "White boys in rock bands just didn't do Aretha songs. But I felt for a while I was in a field of one. For the whole of 1976 I was convinced we were the biggest thing around. I thought I was the best songwriter in the world and we were doing the best live shows. We really rocked."

Even in the middle of the afternoon in front of an audience consisting of a handful of suits from an American record label.

Nigel Williamson

Back to GP album discography