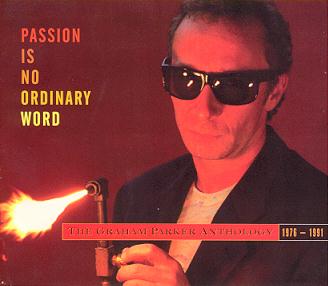

PASSION IS NO ORDINARY WORD: THE GRAHAM PARKER ANTHOLOGY 1976 - 1991, Rhino double CD R2 71425, 9/21/1993, USA

It was never meant to get this out of hand. When I started, I fully believed I was going to

change the consciousness of every individual on the planet earth. But only for approximately

three albums. My task accomplished, I would mysteriously slide into self-imposed retreat,

well-deserved oblivion, or perhaps a mental asylum. Any one of these futures seemed fairly

interesting, even rosy, for they required very little actual work on my part.

Staring at the enormous list of songs on this anthology makes me wonder how I arrived here.

Those idyllic futures had completely evaporated by the time I wrote "Passion Is No Ordinary

Word," and obviously, a life of meditation and navel-contemplation in a castle on the banks

of Loch Ness was just not on. Where did I go right? To my critical hindsight (I'm just staring

at the song titles, not listening to the songs), probably not in enough places.

I wince at the thought of the vocals on "White Honey." Surely I was suffering from advanced

throat cancer? And why on earth did I persist in singing "Question" on "Don't Ask Me Questions?"

Was there some technical problem with the microphone? Was sibilance such a major obstacle in a

1970s recording studio that I dare not pronounce the "S?" And those desperately out-of-pitch

choruses on "Discovering Japan" - what was the producer thinking of to let me get away with that?

And the memory of the ridiculously long bridge section in "You Can't Take Love For Granted" sets

my teeth on edge. And as for "Start A Fire," I just did not need to sing the title three times

on the second chorus. That is so redundant, I could kick myself I could go on, but I'll leave

you to pick out the clams yourself. I can make gallons of chowder out of this lot. This is

supposed to be a "best-of?" Oh, I see - they're calling it an "anthology." Smart move, Rhino!

The wince-inducing sea life notwithstanding, if this seemingly basic human need to compile

dozens of totally disparate songs is unavoidable, then it should be at least executed with the

grace and respect that has gone into this project. The record company actually called me and

asked for my opinions!

"But hey, enough of my yakking," to borrow Marry Dibergi's famous phrase. Why don't you buy this

thing and help me creep into that castle on the banks of Loch Ness? This collection looks like a

lifetime's work to me ... wait, hang on a minute, I'm just getting this idea for a song...

- G.P., May 1993

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the last 20 years of rock 'n' roll knows that Graham

Parker has recorded at least three beginning-to-end great albums: Howlin' Wind, Heat

Treatment, and Squeezing Out Sparks. The trio appear regularly on lists of critics'

and fans' favorites (especially the raw, brutal Squeezing Out Sparks) and remain

high-water marks of what a writer and performer with commitment and talent can accomplish when

he's accompanied by a band just as driven.

But those who limit their enthusiasm for Parker to those three (admittedly out-standing) records

are missing most of the story. It's a tale worth hearing in its entirety, a tale that gets better

with time.

For nearly two decades now, Graham Parker has consistently delivered vivid, barbed rock 'n' roll,

with enough nods in the directions of reggae, folk, and classic pop to sketch the range of his

ever-widening ambitions. He's been pouring it all out with the best of them, and Passion Is No

Ordinary Word: The Graham Parker Anthology (1976-1991) features 39 of his greatest salvos,

including a handful that all but the most obsessive GP fans may have missed the first time around.

Unlike most rock 'n' roll performers who have earned long careers, Parker was no kid when he

recorded his first record. Already 26 and as furious about his prospects in life as his

contemporaries Johnny Rotten and Joe Strummer, Parker saw rock 'n' roll as an escape from a

life pumping petrol, one of his many unfulfilling day jobs after a stretch in a cover band in

Gibraltar and Morocco. Another dead-end career opportunity found him breeding mice and guinea

pigs for scientific research. So the frustration that often gives birth to the greatest rock 'n'

roll had a long time to smolder.

Yet where Rotten with the Sex Pistols and Strummer with The Clash astounded the world by tearing

down rock 'n' roll and dancing in the ruins, Parker voiced his frustration with his life and rock

by claiming for his own the traditional elements that had been forgotten by the dinosaurs then

ruling the charts. Soul, especially the Stax variety, had been all but forgotten, and longtime

standard-bearers like Van Morrison were gradually being confined to cult status. Parker's mission

was to break that unfortunate situation wide open. In 1975, his solo demos caught the ear of Dave

Robinson, who later formed the independent record label Stiff. Robinson, no dope, knew something

new when he heard it and promptly introduced Parker to a band that could make his songs breathe

fire.

The Graham Parker Anthology kicks off with "White Honey," also the leadoff track

from his 1976 debut Howlin Wind, a record that still can set off smoke detectors. It was

immediately apparent that his band The Rumour, a quintet of pub-rock vets led by Brinsley Schwarz

(along with guitarist Martin Belmont, bassist Andrew Bodnar, keyboardist Bob Andrews, and drummer

Stephen Goulding), shared Parker's death-or-glory attitude. They had wandered from pub to pub for

years in search of a fronting vision, and they locked into Parker's songs with a knowing vengeance.

Augmented by a horn section and massaging background vocals, Parker emphasized how much excitement

could be squeezed out of the soul music he had loved so long.

Parker was quickly lumped in with the punks because of his intensity and belligerence, but Parker

was one Brit whose version of revolution included history: He remembers, "I wrote 'White Honey' in

1975, when the fashionable music was still a hangover from the progressive era. There was no

direction in pop music. Some people like David Bowie and The Rolling Stones were still coming out

with actual songs, but most of what was coming out was sub-Bad Company or pseudo-Pink Floyd. I

was listening to Busby Berkeley at the time, and I was very into Van Morrison, who seemed to be

able to incorporate a lot of swing in his music. I'd gone back to the roots of what I was into as

a teenager, which was black soul music, and I combined it with the Busby Berkeley, Hal Rubin, and

Al Warren songs that I loved. That's what I was trying to do with 'White Honey,' with those cutesy

lines and that horn section straight from R&B."

Parker may label some lead line "cutesy," but Howlin Wind is not a light collection.

"There's definitely some angst in 'Back To Schooldays,'" he allows. "It's fairly simple

in what it's trying to say: the idea of what school was supposed to prepare us for and the

reality of what we're living. The song said this whole system is wrong, and I'm gonna show you

where it's at." The song sports a rockabilly rhythm (a Parker rarity) as well as a guitar line

lifted from the Scotty Moore songbook, although the poison-pen lyrics identified the number as

no one's but Parker's. "I'd never been a rockabilly fan when I was young, but about the time

that I wrote that song, '74 or '75, all those rootsy ingredients were coming to me, and I was

feeding off of them."

Overseeing this feeding frenzy was producer Nick Lowe, renowned for his "bang it out/tart it up

later" attitude toward making records. "Nick Lowe wasn't some technical producer there to lord

it over me because I was green," Parker says. "I had only been in scruffy demo studios. I was

just an emotional talent. I thought I was on a crusade; I thought I was about to enlighten the

world with my wisdom. Nick Lowe was just there to capture it and keep everyone grooving.We made

a very good team."

They also made a team that could express the anger of punk without indulging the form.

"Howlin' Wind" emphasized the edgy ska that The Clash would later exploit in a

no-less-incendiary fashion on "White Man In Hammersmith Palais," with its references to

"a strange religion/without any god" and a breeze that could cut down anyone. The apocalyptic

"Don't Ask Me Questions" slammed the debut album to a close with an ominous guitar sliding

from rock 'n' roll into reggae and then back again and a defiant statement of purpose that spared

no one.

Notes Parker. "'Howlin' Wind' and 'Don't Ask Me Questions' have a real feeling of Armageddon,

don't they? I'd been into music as a teenager, and, Bob Marley's Catch A Fire reinforced

reggae for me. I loved how it incorporated modern rock 'n' roll guitaring and some pop melodies.

It felt like what I wanted to do: make intelligent lyrics and catchy tunes. Writing in that style

was natural for me: '007' and 'Shanty Town' by Desmond Dekker were some of the first things I

learned to play on guitar when I was a teenager. I was trying to do everything on that record.

A first LP is very special to a performer, because everything you have goes into it, all your

styles."

Also included here is the first album's Rolling Stones-derived, harsh-yet-soothing rocker "Soul

Shoes," though not in its original version. Shortly after the first album's release, Parker's

British record label recorded a Parker & The Rumour concert as Live At Marble Arch, a

promotional-only record. That collectors' favourite includes this version of "Soul Shoes." As

with the work of other great performers who came of age in the '70s, folks like Nils Lofgren and

David Johansen, Parker's promo-only live LP detailed the intensity and variety of his concert

performances far more persuasively than later, officially released live sets. The guitars on

this version underline how much the songs owes to Keith Richards "Happy."

Recorded only a few months after Howlin Wind, the sophomore set Heat Treatment

(1976) was a real jump in terms of songwriting, performance, and density of production. Parker

now says that producer Robert "Mutt" Lange can be "squarely blamed or credited for the sound on

Heat Treatment. On Howlin Wind the arrangements were strictly by Graham Parker &

The Rumour. For the next record we thought we'd try a producer who liked to arrange. He liked to

tailor songs into hit singles. We thought we'd like some of those."

On Heat Treatment, Parker's affection - and affinity - for soul music rose to the surface,

both in his Stax-derived songwriting and the arrangements. Says GP: "I was very determined to get

soul music to young people again, in part because it was diametrically opposed to the progressive

hangover. I also wanted to get away from the 'new Dylan' tag. I loved the idea of horns,

especially because they were out of fashion."

The album's soul imperative was most evident on "Heat Treatment," a loud, big-production

rocker that cascades on the tension between the soul horns and the band members' impulsive vocals.

It's a track on which Parker's soul-revival dreams come true. "Heat Treatment" also makes clear

how pervasive Lange's influence was on the record. Says Parker: "Back in the '70s, Bruce

Springsteen once asked me, "Who did that really high vocal [on the breakdown]? That's amazing.'

I figured it must have been Bob Andrews, but only in recent years did I realize it was Mutt,

of course." How did he figure this out? "Listen to the high vocals on all those Def Leppard

records he produces. He's all over them."

Other standouts from Heat Treatment include the soul-rocker "Pourin' It All Out,"

of which Parker now only says, "Hey, to be on your second LP after being an obscure kid from the

suburbs all your life, it's a great feeling to be able to pour it all out in public." When he

shouted, "I don't mind telling you/What I'm going through/I don't mind telling you/ 'Cause every

word is true," he summarized his intentions with precision and defiance.

Even more crucial to Parker's career was the album's climatic ballad, "Fools' Gold," a

statement of belief in the face of cynicism that remains the favourite track of many GP fans.

"It's pretty Stonesy. I don't play it much anymore, but it's still pretty timely. It captures a

large drama with those big, open A and D chords. It's an anthem of sorts, I suppose. Some hair

band should record it and bring me real gold." Parker's newfound understatement notwithstanding,

for years "Fools' Gold" was the centerpiece of his live shows, the point in his performance

when he best articulated his hard-headed romanticism. "I'm a fool/So I'm told," he'd sing, and

then wear the appellation like it was his most prize possession.

"Hold Back The Night," a raucous recasting of The Trammps' contemporaneous hit, was first

available on these shores on an EP called The Pink Parker, pressed on guess what-color vinyl.

Recorded by Lange around the time of Heat Treatment, it served as a link to Parker's next

record. "Seeing as I was pushing for the soul horn-section thing, I wanted to do a whole EP in that

sort of style," says Parker. Even more important, the recording emphasized how little he cared

about appearing trendy. As he recorded "Hold Back The Night," The Trammps had begun moving to

straight disco (their "Disco Inferno" was imminent), a form considered anathema by most rockers.

But Parker knew a great song by a great group when he heard it, and damn the trend-makers. Peaking

at #58, a single version of the song became Parker's first charting single in the States - and his

last one for six years.

Next up was Stick To Me (1977), which was nearly a disaster. The album was recorded with

producer Bob Potter, whom Parker picked after hearing a Grease Band record that Potter had

engineered. Although Parker was pleased with Potter's work, it was not Potter's version that

eventually came out. "There was a big problem on the tape: Oxide was coming off. There were many

accusations of neglect leveled at the studio. It was a dreadful streak of fate. I thought the

record was done, but then we couldn't mix it. It wouldn't balance and there was black stuff

coming off the tapes. We had only a week to redo it [with Nick Lowe back at the helm], because

we were scheduled to go on some Scandinavian tour or some nonsense that was part of my manager's

plan to keep me on the road all the time."

On the original version of the record, Parker & The Rumout cut some tracks alongside a

50-piece string section. "We had to cut that by half for the redo," Parker says. "Those songs

were much more lush before. At the time, I wanted to incorporate more grandeur into our music.

The war cry in the studio was 'grandiose and Vangelis!' I know that some people think the album

sounded pub-rock, a movement that I was definitely not a part of. The released version of

Stick To Me is very much live takes, grungy-sounding. I liked it because it was so nasty,

but it was not meant to be like that at all."

Some of the Stick To Me tracks burst through the hurried mixes with the excitement of a

group sure of their mission, even if they all had an eye on the studio clock. "Stick To Me"

in particular was as aggressive as anything the band had ever recorded, with guitar solos jostling

against a string section that pushed back just as hard, urging everyone to even higher gear. The

down-tempo "Watch The Moon Come Down" piled up influences as diverse as The Drifters and

Bruce Springsteen, adding up to a statement of solitary reflection as enticing as "Up On The Roof"

and as frightening as "Backstreets." The combative "Thunder And Rain," built around Schwarz's

forbidding lead line, treads near the punks' turf of nihilism, with only a hint of accommodation.

Nowadays Parker considers Stick To Me a salvage job, the best the group could come up with

in such a short amount of rerecording time, but even a cursory listen suggests that his vision was

so focused that nothing, not even oxide-shedding tape heads, could stop him.

Next up for the road-locked unit was The Parkerilla, a double-live set and a terrible

disappointment, especially to those fans who had been lucky enough to find Live At Marble Arch.

"We were a pretty popular live act, into the 3,000-seat theater range. It was the logical, boring

thing to put out a live album to satisfy the fans." The skimpy set, which included on its fourth

side a weird disco remix of "Don't Ask Me Questions," was the final straw that cracked Parker's

never-smooth relationship with his first record company.

Furious that his records were being promoted passively (to put it kindly), Parker got out of his

deal and promptly wrote a song about the experience "Mercury Poisoning." Says Parker, "My manager,

the brilliant Dave Robinson, suggested that in our hatred for Mercury we should do a whole LP

slandering the record company, all vitriolic songs squarely aimed at Mercury. I wrote this song

in half an hour, and we recorded it at the same time as the Squeezing Out Sparks songs."

But for all its horn-driven energy, "Mercury Poisoning" seemed a bit flip compared to the other

songs he was writing for that album, and it was stuck on a promo 45 that preceded the first

official release on Parker's new label, Arista.

A memorable B-side from this period was a bellicose take on "I Want You Back (Alive)."

One critic at the time suggested Parker sang The Jackson 5's signature tune as if he was

repossessing a car. Counters GP, "We recorded it on a mobile in a rehearsal room while rehearsing

for Sparks, in a real grungy place in London. I thought it was very musical - now it sounds

like World War III is going on in there. But then again, Stick To Me sounds like murder

now." In 1991, Parker wrote, "I met Michael Jackson not long after and told him I had done a

version of the song. He looked at me like I had just spoken to him in an alien language."

Squeezing Out Sparks (1979) redefined Graham Parker & The Rumour. Of all his records,

this is both his best-selling and his most cherished. Backed against the wall once again, Parker

& The Rumour delivered a set that rightly remains one of the most acclaimed rock 'n' roll

records ever. Terse and raging, they had arrived somewhere new and could not be denied. No longer

merely a gifted soul proselytizer, Parker finally found his own voice.

Nowadays Parker underplays his achievement, preferring to dwell on what he considers the

collection's sonic shortcomings: "I just wrote a bunch of songs, and [producer] Jack Nitzsche

produced it without too much attention to detail. The bass drum is louder than the bass guitar,

which isn't very pleasant." But he does allow that a change had come: "These songs were entirely

my own creation. They didn't have the mess of influences that artists carry with them when they

start their careers."

This new, stripped-down style of songwriting was ideal for The Rumour. Freed from keeping pace

with Parker in a sonic flurry of multiple horns, keyboards, and vocal lines, they played as

directly and tautly as Parker wrote and sang. The set exploded with the dangerous "Discovering

Japan," an outstanding evocation of all sorts of dislocation. I had been to Japan on a tour.

A song can start from one phrase. One Japanese girl said she had read a book called My Heart Is

Nearly Breaking." So Parker wrote the first line of the song, "Her heart is nearly breaking,"

and he was off. "I was in a very high-powered period. We were doing too much touring. I didn't

have a home. I'd been through lots of time zones, lots of relationships, seen lots of bizarre

things. But this was not your ordinary hotel-room song."

Lighter on the surface but even angrier inside was "Local Girls." Recalls Parker, "This

goes back to my youth - looking outside the window in one's hometown; looking at all these girls

you can't get at. The whole thing was very sarcastic. It's a light and breezy pop song, but

there's definitely some hatred in those lyrics for the local girls." An AOR favorite, "Local

Girls" became Parker's first official Arista single.

The most controversial number on Squeezing Out Sparks was the song that gave the record

its title: a tight-lipped acoustic horror tale, "You Can't Be Too Strong," a song about obligation

and responsibility that spares none of its characters, including its narrator. "There's nothing

really to add to this song," says Parker, weary of discussing the specifics of its story. "I get

fairly rankled when people ask whether it's pro- or antiabortion. I don't deal with such

simplicities. It's about being involved in an event." The circumstances of writing the song were

ironic, considering its sober topic and presentation: "I had been out to Guildford University to

see Wreckless Eric. I got up and sang 'Johnny B. Goode' with him. I was fairly out of head. I was

staying with my parents at the time, and when I got to their home, I wrote it."

Also on Squeezing Out Sparks was "Passion Is No Ordinary Word," a statement of

purpose in the mode of "Fools' Gold" that made the fight against cynicism sound like the most

thrilling act imaginable. "Those ascending chords provided the push," Parker says, still pleased.

"It's great when you come up with those chords. That guitar riff is so lonely, so yearning."

Although the word "passion" means less every time someone sings it, couplets like "When I pretend

to touch you/You pretend to feel" put across the idea with venom and precision.

Squeezing Out Sparks was by far Parker's best-selling American record, peaking on the

Billboard chart at #40 (his previous best-seller, Stick To Me, only fought its way to #125),

and this relative commercial success made Parker confident enough to enlist an American producer,

Jimmy Iovine, to shepherd his next record, The Up Escalator (1980).

Says Parker, "We chose Jimmy Iovine because my manager raved on and on about the drum sound on

[Patti Smith's] 'Because The Night.' Back then, recording was still a mystery; how you got a great

drum sound was still a mystery. By the time we finished a tour, we always hated the last record.

We knew the next one had to sound great. We used to talk about sound all the time and how to get

it right. Now you can just press a few buttons on a rack and get a great echo on a snare. I

remember that when we picked lovine, Tom Petty was on the charts with a record that Iovine had

produced, at a time when radio in America was all Eagles and Fleetwood Mac. Grungy English music

wasn't getting played. We wanted to fit in. And Iovine was a big fan of my records. He had pursued

me. It seemed like a good match, but now it doesn't sound like what we thought we were going to get.

"No Holding Back," a straightforward pop song, kick-started the assault on American

air-waves. It was noticeably softer than the Sparks songs, but still mixed unease and fear in

with the apparent good cheer. Upping the ante was the mind-your-own-business single

"Stupefaction," which grafted happy chords and background vocals onto lyrics like "Why

are you so stupid?" "That song definitely came from spending a lot of time in Los Angeles,"

Parker acknowledges, and although the idle-rich targets might appear a bit obvious in 1993, back

in 1980 it was thrilling to hear such unapologetic iconoclasm. And, yes, the drums did sound great.

But the strongest track on The Up Escalator, "Empty Lives," recalled the focused

fury of Parker's previous record. "That's very dangerous, I suppose, to tell your audience from

the stage they have empty lives. It's harsh stuff. In hindsight, I'd rather have had this on

Sparks than 'Waiting For The UFOs.'" All staccato guitar outbursts and ferocious drums,

"Empty Lives" emphasized that even Parker's more pop-oriented records were not always safe places.

The Up Escalator was intended to be a commercial breakthrough, so of course it wasn't - it

rose no higher on the charts than Squeezing Out Sparks and spent two months less time

there. Parker responded by trying to make an even slicker record, at least in part because he

and The Rumour were parting ways. "The Rumour logically had come to the end of our existence as

a unit," he says. "I'd had enough of the grunginess, the constant push and pull of everyone

wanting to play at the same time. It was a great wave of relief to do something very pure, plain,

clear, not full of aggression." (The members of The Rumour went on to perform extensively as a

unit and separately, most impressively as the backing band for Garland Jeffreys' tour supporting

Escape Artist.)

Parker's resulting album, Another Grey Area (1982), was every bit as slick as he wanted,

thanks to coproducer Jack Douglas, to whom Parker deferred on everything from arrangements to

personnel. "I had a major record deal with very large advances. I thought that was the way to

make records. Douglas fit into that, with his attitude of 'I'll show up at the studio at 5 p.m.,

not 1 p.m. when I'm expected, but I don't care, because I've been up all night mixing someone

else's record.' The album cost $375,000 to make, almost $200,000 over budget. In England, this

was the end for me. They're touchy about people coming to America and using session musicians.

I suppose this is not as exciting as what I did with the Rumour, but the record had some gems.

Two of them are here. The georgeous ballad "Temporary Beauty" fit in perfectly with

Douglas' high-tech, glossy style, with more nods to Motown than Stax, and it inspired a

particulary hilarious promotional video, in which GP cavorted among giant blocks of ice.

"Another Grey Area" came within shouting distance of the high-energy barrages of the

past, and as Parker points out, "it does have a couple of rhythmic changes that are pretty cool."

Pianist Nicky Hopkins built the foundation of a track that annihilated charges that Parker had

gone "soft."

The Real Macaw (1983), Parker's final set for Arista, was at once both his most pop-oriented

record and his most experimental. Rumour stalwart Brinsley Schwarz returned on "orange and black

guitars," yet Parker was looking forward. "When I was younger in the business, back in the '70s,

a year seemed like a long time. Everything I did seemed like major event. By the '80s I was

cruising a bit more. You can hear that here. This album had a lot of quirkiness and experimentation.

Someone brought an Emulator to the studio, and [producer] David Kershenbaum wanted to use a drum

machine. We tried everything."

The Real Macaw was Parker's "happiest" record to that point, though he was careful not to

let happiness be an excuse for sappiness. Standout pop songs from the set included the reflective

"You Can't Take Love for Granted," characterized by a surprisingly supple vocal and later

covered by power-pop chanteuse Marti Jones, and the atmospheric midtempo love song

"Anniversary." Parker today is fondest of the synthesizer-driven "Life Gets Better,"

his first totally successful hopeful-about-the-future pop song. Included here is the original

single that was issued in the U.K. preceding the LP. It features an ethereal vocal intro that was

eliminated from subsequent versions. The American single snuck into Billboard's singles chart for

two weeks, inching up to #94 before falling off. Of the song, Parker says, "Sure, we were trying

to cut a pop single, but that was no different from what I was trying to do when I did 'Local

Girls.' I suppose this one doesn't have much resonancel but it's not that soft."

Much less soft was the promising Steady Nerves (1985), which turned out to be Parker's only

record for Elektra. Parker and coproducer William Wittman "were trying to get aggression back into

the production. We tried to make it big." The record was credited to "Graham Parker & The Shot."

The Shot was essentially the Real Macaw band, though this time they did sound like a band,

not a pack of session folks. "Break Them Down," which Parker calls "one of my rare songs

about something specific," was a damnation of fundamentalist imperialists (the type of missionaries

who label their victims "savages") that was as effective as the condemnation of lesser evildoers on

"Mercury Poisoning." Parker was angry again, and it lifted his music another notch.

From the other side, "Wake Up (Next To You)," made Parker's soul dreams come true for the

first time in years. "This is everything I wanted to write, nothing about worrying about what

Graham Parker is supposed to write about. Smokey Robinson could have written this. My aim is to

write something like 'Just My Imagination' or 'Being With You.' That's perfect songwriting. They're

love songs, but nothing about them is embarrassing or cringe-inducing." Nobody cringed: This single

edit became Parker's first American Top 40 single.

Having reestablished himself as a top-rank talent, Parker promptly fell off the radar screen for

three years. He left Elektra for Atlantic, where he recorded the demos for the songs that would

make up his unequivocal comeback, The Mona Lisa's Sister (1988). "I was starting to grow up

and realize that you have to do more to achieve more. You can't let a producer define your sound.

So I called myself producer and wrote songs that were more like my earliest records in attitude.

Atlantic wanted me to break out with a big-selling record. They wanted to work in that direction,

get all stick again. But if you think like that - as I had - it will backfire. I told [Atlantic

head] Ahmet Ertegun that I had tried that. I went with Iovine, Douglas, and Kershenbaum when they

all had records in the charts, but I still came out sounding like Graham Parker. The new songs

sounded so good on demos, so full. I wanted to stay close to that."

Since then he has, with remarkable consistency. After parting ways with Atlantic, Parker forced a

career shift that has carried him ever since. While he has regained much of the spirit and the

wildness of his earliest records, he has done so by openly disparaging the rock 'n' roll myth that

he had lived so long. His music became more subtle, down-to-earth, and his lyrics revealed someone

more vulnerable and reflective. Perhaps part of the reason for the shift is the natural difference

between a writer in his twenties and the same writer in his forties, but for whatever reason this

apparently permanent reinvention has allowed Parker to reach the heights again, more on his own

terms than ever before.

RCA started a four-record affiliation with Parker on The Mona Lisa's Sister, of which Parker

asserts, "Here you can hear that the drive is back." On this record, Parker stuck to his

once-and-future most fruitful backup, the small, self-contained band, including Schwarz and fellow

ex-Rumour Andrew Bodnar on bass. Aroused midtempo songs like "Don't Let It Break You Down"

(the shiny riff of which dated back to the '70s) were the rule, and numbers like "Back In

Time," with its tumbling of semi-autobiographical lyrics, pivoted on spare, taut rhythms and

the viewpoint of a man whose skepticism had become kinder, if no less specific. "Get Started,

Start A Fire," a Spinners-sweet rock-radio favourite, "was written as a 'Miss You' groove. I

had to get strange things into it," including an impenetrable assertion that Joan of Arc was done

in by anti-smoking laws. "It's not about me. It's real writing."

The follow-up, Live! Alone In America (1989), was an early entry in the "Unplugged"

sweepstakes and one of the few in which the performer was working without an obvious net. "I

didn't know what to do next, so I decided to take a chance. My whole career has been rock 'n' roll

or pop, which you do with a band. Because Mona Lisa was a more stripped-down production

based on acoustic demos, I figured I'd do a two-week acoustic tour and scare myself." The

previously unreleased punky reggae finger-pointer "Soul Corruption" was a high point of the

solo shows and the resulting album.

Parker considers Human Soul (1990) "an in-between kind of work. I didn't try to do anything

outstanding in a production sense. I didn't try to take any risks. I just recorded songs in a

traditional lineup and enjoyed doing it, though the second half has some weird songs to the left

of what I normally do." Indeed, the second half (second "side," in the old vernacular) was composed

of short, strung-together numbers that commented on each other in fascinating ways without

deteriorating into strained "concept-album" connections.

Parker calls the sweet soul rocker "Little Miss Understanding" "a fun track to do, a

throwback to Heat Treatment mode. 'Big Man On Paper' has a lonesome feeling to it,

and I might add that it's very popular in upstate New York because it mentions the Hudson Valley

Mall. And 'My Love's Strong' is my sort of soul ballad. If Rod Stewart or Paul Young

recorded it, I'd have a large amount of shekels rolling in, I dream." Throughout the numbers on

Human Soul, all put across without an ounce of extra baggage, Parker hinted that he might

be onto something new.

If Human Soul was a transitional set with occasional gems, Struck By Lightning (1991)

delivered 15 consistent explorations; Parker calls it "the best record I've ever made." A

three-piece core band - Parker, Bodnar, and Attractions drummer Pete Thomas - wrapped itself

around a series of cogent songs that "have that strong feeling of mood that Neil Young manages to

capture with alarming regularity. It was very simply recorded. I've finally figured out how to make

these kinds of records." This anthology includes the circus rocker "They Murdered The Clown,"

introduced by a cheerily psychotic organ; the observational ballad "Strong Winds," which

owed much to Neil Young's brand of doomful optimism, and "The Kid With The Butterfly Net,"

a violin-driven slice of pastoral life that suggested the album's cover. They're all great songs,

as sturdy as any recorded that year, but Struck By Lightning is a work best heard in its

entirety, where the numbers comment on each other in surprising ways.

The Graham Parker Anthology concludes with "Museum Of Stupidity," an outtake from

Struck By Lightning that appeared only on the vinyl U.K. configuration of the set. Hurriedly

recorded, banged out in one take like most of Parker's choice recent work, "Museum Of Stupidity"

takes on some of today's most heinous music-industry morons (both the PMRC and The 2 Live Crew get

what they deserve) with all the wit and anger you'd expect of an aging iconoclast. But this isn't

"Mercury Poisoning" redux. Although one freedom-smashing censorship group and one unusually bad pop

unit get mentions here, the song is not solely about some pop-music battle. As the song builds, it

expands to take on all sorts of folks with an interest in limiting freedom (the religious right, in

particular), and in the end, Parker turns the venom on himself. It's the work of a grown-up who's

anxious to ignore petty issues and turn against the larger injustices that are worth getting angry

about.

"Now wait a minute," Parker says. I don't consider myself an iconoclast. I consider what I write to

be pop songs. I think they're very commercial, very mainstream. A lot of times I think, 'This is a

catchy ditty with some interesting words. It's a hit.' And then it sticks out like a sore thumb."

Parker still sticks out in engaging ways. A 1992 record for Capitol, Burning Questions,

expanded the previous record's concerns, and Parker is currently ensconced somewhere in New York

working on book called HATEMAIL. Says Parker, who long ago published a sci-fi/comedy novel

called The Great Trouser Mystery, "The new book started off as straight ranting, but now

there are stories and observations to go along with the scathing indictments." Watch out. He's

still searching.

- Jimmy Guterman

|

disc one |

disc two |

|

|

|

All songs Written by Graham Parker and Published by Geep Music, Ltd. ASCAP, except: "I Want You Back (Alive)" by The Corporation (Berry Gordy Jr., Alphonso Mizell, Frederick Perren & Deke Richards), Published by Jobete Music Co., Inc. ASCAP |

|

sources/personnel: |

|

|

Compilation Produced for Release by GARY STEWART & BILL INGLOT

Compiled by GARY STEWART & CLIFF CHENFELD

Research: GARY PETERSON, PATRICK MILLIGAN

Remastering: BILL INGLOT & KEN PERRY

Art Direction: GEOFF GANS

Design: DOUG ERB

Design Assistance: RACHEL GUTEK

Photos: JOLIE PARKER, GODLIS, GREG ALLEN

Special Thanks: BILL LEVENSON

Back to GP album discography